How to make a classroom full of children – often from completely different backgrounds – effective for students and teachers? And what is the approach to mobile phone use at school? For the first Czech edition of Running the Room: The Teacher’s Guide to Behaviour, we interviewed its author Tom Bennett. „I think it’s an odd way to try to get people to behave – hoping that they will do so because they want to,“ he says for EDUkační LABoratoř.

Why would a nightclub manager change their career to become a teacher?

Running clubs was exhilarating but very unsatisfying. Eventually it wasn’t enough to feel like you were running a party for everyone else; I wanted to do something that made a difference, that gave something back to the world, and that used my mind. When I saw the advert on TV to become a teacher, it felt like a light switch had gone on in my head. It seemed the obvious choice. There was no dilemma or struggle for me. It felt like it was where the universe needed me to be.

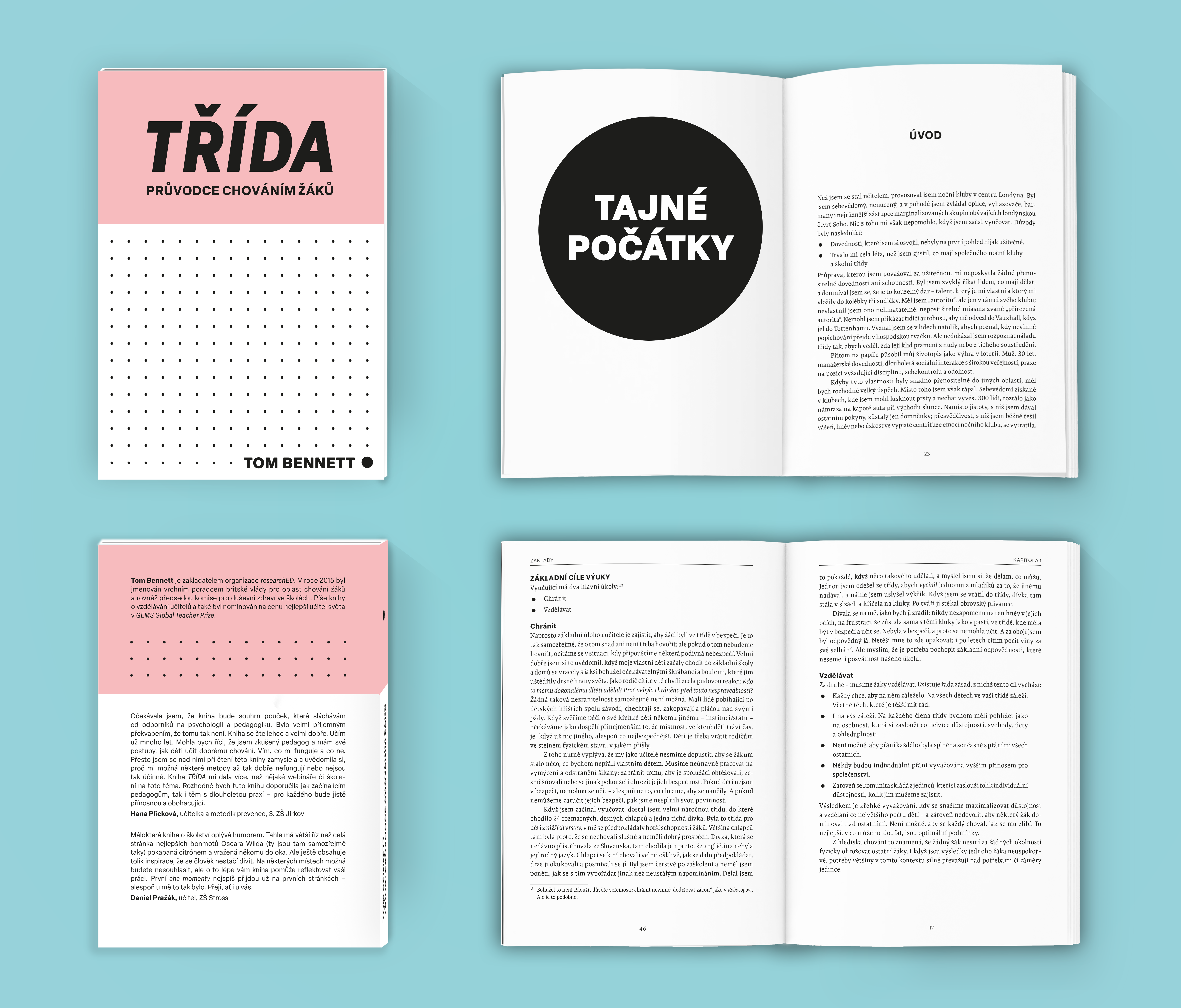

Tom Bennett is the founder of researchED, a grass-roots organisation that raises research literacy in education and campaigns for better evidence awareness worldwide. It now holds events in six continents and 13 countries, attracting thousands of followers and generating discussion and change in schools throughout the world. He is also the editor of researchED magazine, with over 15,000 global subscribers. In 2015 he became the UK government’s school ‘Behaviour Czar’, advising on behaviour policy, as well as chairing the Mental Health in Schools panel. He has written four books about teacher training, and in 2015 he was longlisted as one of the world’s top teachers in the GEMS Global Teacher Prize. In the same year he made The Huffington Post’s ‘Top Ten Global Bloggers’ list. He is also the Director of Tom Bennett Training, which supports teachers and schools around the world in creating healthy behaviour cultures. Tom is a Teacher-Fellow of Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge.

tombennetttraining.co.uk

X: @tombennett71

After spending some years in the classroom, you moved into writing and consultancy. The latter role has also included working as an advisor for school behaviour to the UK’s conservative government. Would you consider your approach to behaviour conservative?

Although politics affects everything, and it is possible to see everything as a political act, I am clear that doesn’t mean that everything is party-political, or affiliated to any one party of ideology. You could easily argue that the current UK conservatives are anything but conservative, if that means to conserve, to preserve traditions and to change slowly. My behavioural approach is liberal, because it seeks to maximise the freedom available to students in a school community as long as it doesn’t restrict the safety, success and flourishing of others. But it also recognises the importance of the needs of the community in balance with the needs of the individual. It also emphasises the need to centre the safety and dignity of the individual student. Where that locates me politically is anyone’s guess. Usually when someone agrees with me, they identify me as one of them, and when they do not, they identify me as one of ‘those over there’!

In 2020, your view on initial teacher training in England with regard to behaviour management was rather negative. Despite the significance of this topic, it did not get the amount of attention and practice it would deserve, you wrote. Has there been any progress since?

In the UK, and by that I mean England, there has been considerable progress made, largely because of the campaigning efforts of teachers, voices like mine, and a small set of sympathetic ministers and politicians who recognised what was at stake. Last year I rewrote the behaviour guidance for schools to follow, as well as other key documents like the exclusions guidance and mental health guidance. There has been some reform of teacher training requirements, and OFSTED (our school inspectorate) now assesses school behaviour based on this guidance. So in this regard, at least, I think England now leads the world in how it trains teachers to manage behaviour, And we still have a long way to go.

Seen from mainland Europe, English schools often appear more rigid and strict than in the rest of the continent. Compulsory uniforms, short or nearly no breaks, detentions and exclusions for minor misbehaviour such as low level disruption or forgotten homework. A school culture that one may not expect in a liberal country. Is this the reality of mainstream schools in England, or rather a media image?

Schools vary in their approaches. Uniform is a debate that rages around the world, and it must be said that uniform is something that does seem very British. But it is part of our culture, and if we are to have any kind of dress code, then it is probably important to make sure the dress code is followed, as it would be in any other place of work. UK schools provide lots of breaks, I think! There are probably more penalties, but any community has them as one possible response to persistent misbehaviour. If you don’t then some children, maybe 5%, think, ‘Well I just don’t have to do this.’ Which are usually the ones who need the education the most. So, unless you want to entrench social disadvantage, you need to have mild but consistent sanctions as part of a healthy whole-school strategy to manage behaviour. When you don’t provide this kind of structure, you don’t have liberty; you have slavery to one’s momentary preferences. That is disastrous to children who come from chaotic or neglectful environments.

In Running the Room, you write about establishing norms and building a school culture. One of your central messages says that school behaviour must be taught explicitly. Your classroom’s walls would most likely show lists of rules rather than motivational phrases such as “You are unique!”. Don’t you think your approach may not be granting enough freedom and individuality to your pupils?

Lists of rules on the wall are useless unless they are taught. And being taught something is a way to help students to be successful in the complicated world of institutions like schools. When we don’t teach these behaviours, we abandon children from the worst socio-economic circumstances to their fates. Teaching someone how to drive, for example, liberates them from having to walk everywhere. Teaching someone how to speak another language frees them to travel more broadly. Not teaching children how to behave is a dereliction of our duty as adults. Children need us to guide them into independence.

Your suggestions to teachers include numerous measures based on extrinsic motivation such as routines, rituals, rewards and sanctions. In Czechia, some teachers try to avoid extrinsic motivation and rely on intrinsic motivation only as a means to secure pupils’ success. How would you respond to this objection?

I think it’s an odd way to try to get people to behave – hoping that they will do so because they want to. Because what if they don’t want to? What then? My approach uses both intrinsic AND extrinsic motivation. I teach children how to behave and I teach them why the behaviour matters. Then I habituate them into the behaviours so that they feel comfortable and automatic in their actions. But if they do not choose to behave civilly and kindly, then they can expect a formal consequence for their action. And this is exactly what we do in society. We teach people how to behave in public, and we attempt to steer them into behaving well with others, but if they do not, then there are penalties. Show me a society that does not have this! That is why it is strange to think we can do this in schools. We have to use both.

“Every behaviour is communication” – a popular assertion, widespread not only among teachers. However, you disagree. Why?

Because it is trivially true. Everything can be communication in the sense that we can learn something from it. But what if the behaviour is communicating exactly what appears to? What if a child swears at their teacher, or sexually abuses a peer? What are they communicating? The desire to see everything as a communication leads teachers to believe that they can somehow unearth some mysterious unmet need that we then have to meet, and the behaviour will be remedied. But this is simply untrue. Most misbehaviour is not the result of something mysterious, but a result of a perfectly normal human emotion and desire, like status, entertainment etc. Teachers simply don’t have time to be psychiatrists in the classroom. It’s incorrect and inefficient. If a child has some deep-seated psychological trauma, then that can only be resolved with specialist help outside the classroom, not by the teacher.

How should teachers approach socially disadvantaged pupils when it comes to behaviour? Knowing a pupil comes from an unstable family environment, should teachers lower their expectations for them?

Absolutely not! The belief that children form poor backgrounds can’t achieve damns them. What they often need more than most are classroom environments with clear expectations, taught behaviours, boundaries, consistency, safety and predictability. They need the behaviour curriculum even more than everyone else. And they can learn that they are valued, that they matter, that we believe they can achieve, and that they are human beings who can become the captains of their destiny. And of course, that might mean extra help learning these protocols than some others, more persistence, more meetings. But at the heart of it, the behaviour curriculum is what they need more than everyone else.

Is there a golden set of rules concerning behaviour management that should be applied in every school? And if so, what would these be?

I summarise these in my book. I call them the Principles of the classroom. They are:

1. Behaviour is a curriculum

2. Children must be taught how to behave

3. Teach, don’t tell, behaviour

4. Make it easy to behave and hard not to

5. No one behaviour strategy will work with all students

6. Relationships are built on trust, which is built on structure

7. Students are social beings

8. Consistency is the foundation of all good habits

9. Everyone wants to matter

10. My room, my rules

In English schools, your approach to behaviour is often paired with explicit teaching and teaching for mastery. Our readers may already know that these are informed by cognitive science and teacher effectiveness research. What evidence do you use to support your suggestions?

Everything I write about and advise is rooted in two things: practical experience of successful classrooms, and the psychology of human interactions. The entire field of behavioural psychology supports what seems to work best in classrooms: writings on conformity, social proof theory, behaviourism, status, identity etc. underpins these basic ideas. The beauty of this approach is that, because it is also pedagogical in nature, it can borrow evidence bases from the psychology of learning, i.e. Rosenshine’s principles, Cognitive Load Theory, what we know about retrieval practice and so on.

Earlier this year, use of mobile phones in schools was banned in England, with further countries joining this policy. In Czechia, voices calling for more rigorous regulation have become stronger recently. So far, schools are responsible for introducing their own rules. What is your take on this?

Schools should ban mobile phones, from gate to gate. There is no question in my mind about this. They have an enormous impact on three areas:

1. Learning. Smartphones are designed to be black holes, sucking in your attention. But attention and focus are very much what we are in the business of in schools. Even worse, they have a greater impact on children who are the furthest behind.

2. Safeguarding. Children are exposed, unsupervised, to every horror, pornographic image, and inappropriate content we can imagine. Why on earth would a sane adult expose children to that? Even if you trust your child, there will always be children who use it for horrible purposes next to them. Sexting, cyber bullying etc. are all a normal and horrible part of too many children’s lives.

3. Socialisation. When children are on their phones, they are not present in the social environment. They do not learn to interact with one another as social beings. They retreat into virtual worlds that feel safe and secure but are actually a prison.

Schools that ban mobile phones never regret it. I have worked with hundreds that have done this, and while it can be hard at first, students, staff and parents overwhelmingly support it.

What should alternative schools, or simply schools which value freedom over rules and order, learn from your book?

You cannot have freedom without boundaries of behaviour; if every child is free to do as they please, some will choose to terrorise others, to victimise, or harass, or simply opt out of learning. That’s not freedom, that’s the tyranny of the strong and merciless. Every society needs to have boundaries, and every boundary must be patrolled with possible sanctions, But these are not the only things we need; we also need behaviour to be taught; we need children to know that they are valued, that they matter to us, and that because we care about them, we will protect them from one another until they are capable of making caring and sociable decisions with one another. When we don’t do that, we abandon them. They need us. They have always needed us. So we need to be adults, and face up to our responsibilities.